Fostering accountability through board evaluation: the first step to improving the executive recruitment process

Madrid, Spain – Accountability is one of those buzzwords that is often tossed about as essential in the business environment. However, in many cases only lip service is paid to an ideal that few companies actually meet. The fact is that accountability must be top-down; regardless of the company's size, industry or ownership structure, the board must assess its own performance in meeting the company’s goals.

Over the last two decades, oversight failures have been seen literally "across the board" – in listed companies, state-owned enterprises and third-generation family businesses. Board evaluation, therefore, needs to be more than a mere box-ticking exercise.

Many national corporate governance codes include a recommendation to conduct an annual assessment, and an external evaluation every two to three years. Directors should not approach this as a burden but as an opportunity to assess the risks to the Board in key areas in order to conduct the necessary changes.

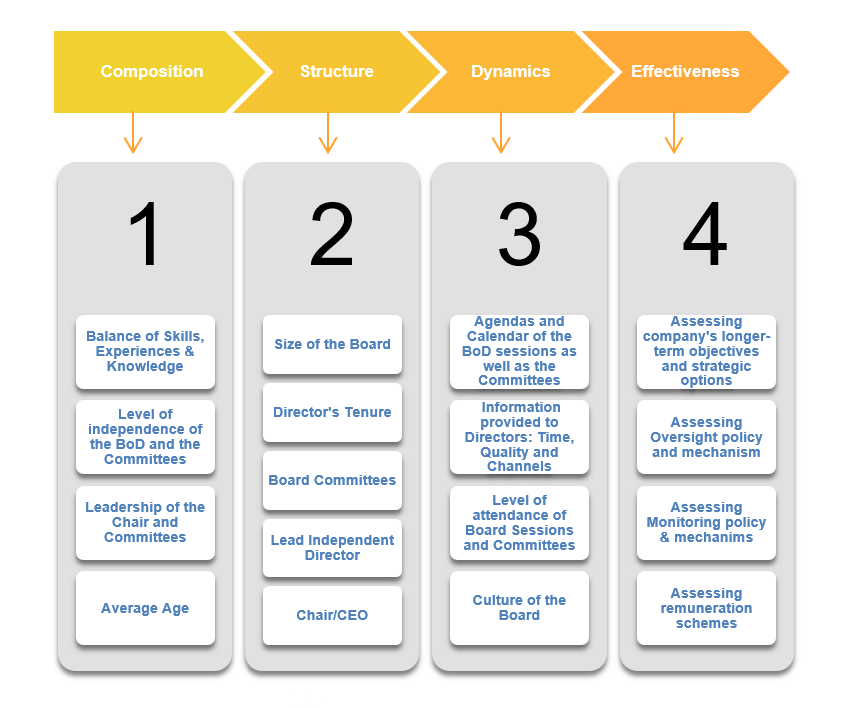

The main areas for assessment are shown in the following graphic:

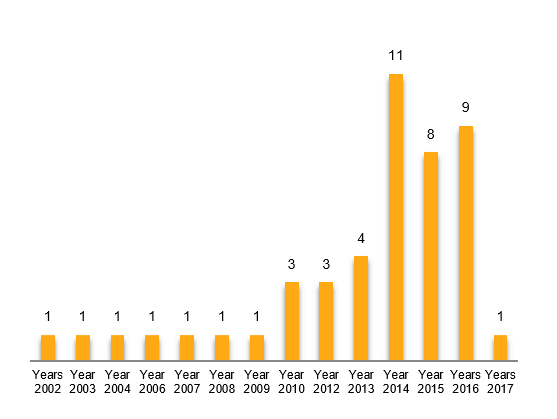

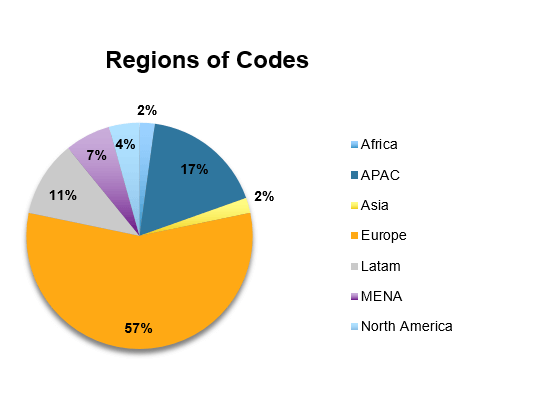

Accountability and board evaluation are best-practice concepts that are recognised around the world in the national corporate governance codes of OECD and Non-OECD economies alike. We analysed the national corporate governance codes of 46 countries [1] and found that in every case except one, there was an explicit reference to the importance of the board evaluation, whether through regulations, private initiatives or consensus between stakeholders [2]. The graphics below shows the ages and countries of origin of the national corporate governance codes that we included in our analysis:

A considerable number of these national corporate governance codes embrace the importance of “Diversity” in board composition. This is a key factor for effective decision-making, and contrary to popular belief is not limited to gender. Critical aspects such as skills, knowledge and executive expertise must be assessed to ensure that the board has a true balance. The importance of board evaluation is partly due to its function in helping governing bodies to assess whether there is any excess or shortage of certain profiles to fulfil the company’s strategy and challenges.

In 2016, the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University and The Miles Group published a nationwide (US) survey of 187 board directors of public and private companies. Most of the key findings are valid for emerging markets in which board evaluation practices are not yet universal.

The skills which were rated most favourably in the survey were: 1) Financial skills (85%); 2) Management experience (82%); 3) Industry experience (81%) and 4) Audit/Accounting (81%).

Conversely, directors gave the lowest ratings for: 1) Technical knowledge (47%), 2) Cybersecurity (18%) and 3) Social media (16%). These numbers are shockingly low if we consider the increasing importance of digitalisation and cybersecurity, and the dangers of failing to meet these challenges.

The board evaluation process should not be intended as a witch-hunt, but to enable companies to readjust their board matrix and refine the nomination and appointment processes. Once the company defines its goals, a series of new questions are raised. Who should conduct the board evaluation? How should the evaluation take place? Who is qualified and able to make decisions? In order to implement an effective system of evaluation, several questions need to be answered before any steps are actually taken.

Frequency of the evaluation cycle

There must be a set evaluation period; although an annual cycle seems the most obvious and ubiquitous, it may not be the best for every enterprise.

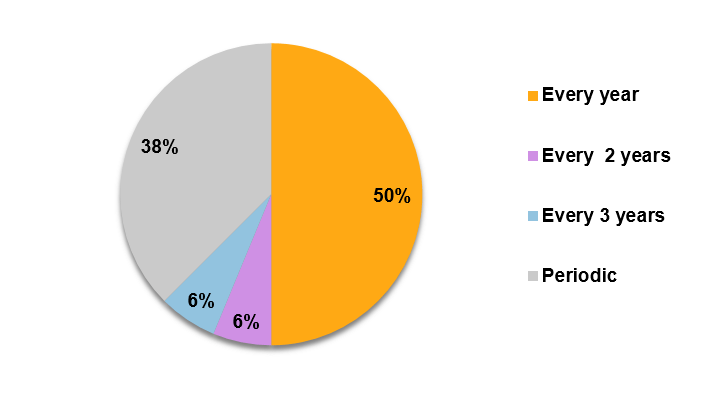

Governance codes often suggest that boards should carry out self-assessment at least once a year. Moreover, investors' guidelines and proxy advisors' voting policies frequently expect companies to bring in an independent advisor to assist or conduct an external board evaluation at least every two or three years.

The chart below shows that 50% of the national corporate governance codes suggest an annual evaluation, often referred as self-assessment, while 38% are more vague and state that the evaluation should be “periodic,” while not giving a specific timeline. For example the codes in France, Russia and Slovenia combine an annual assessment with a triennial evaluation, often suggesting that a third party be involved for the latter.

The board should set out the process in a formal manner, establishing the timetable, methodology and level of disclosure.

As previously stated, some flexibility must be provided. If the purpose of the evaluation is to offer information to make suitable adjustments, it seems only natural that when the company or the business faces geopolitical, strategic or risk changes, the board should dedicate sufficient time to considering whether they need to adapt the director profiles, create new committees or enhance communication with management, eventually setting up a one-off evaluation process.

Some businesses may find it better to evaluate the core goals over a longer period of time, setting medium-term milestones for its decision-makers and key executives, with long-term compensation policy and incentive plans where appropriate. On the other hand, smaller companies and businesses in fast-changing industries may need a shorter period to react flexibly. However, the most common system is for the board to be regularly evaluated in order to update the performance plans and adjust as needed.

The strategic pipeline may also impact the board evaluation cycle. For example, PwC conducted a survey [3] in 2016 among 884 public company directors, who were asked: “When the board is discussing company strategy, what time horizon is primarily used?” The response was: 41% one to five years; 43% one to three years; 10% one to more than five, but less than ten years; 5% one year and 1% one to ten years or more.

Individual members or the board as a whole?

This is a key aspect going back to the basic idea of accountability. Is the board as a whole responsible for fulfilling its goals, or are individual members responsible for specific enumerated areas and tasks? Many factors can play into this decision, including the size of the company and the regulatory requirements. However, this question does not require a binary answer. Some goals could be left to individual directors; some could be tasked to the board as a whole, and others could be assigned to groups of directors. We must never ignore that the board as a whole will be accountable, not only by law but in the eye of shareholders and moreover, the media. A board that allows individuals to underperform or mismanage will be perceived as one that failed in its oversight duties.

Both of the surveys quoted here seem to show a perception from directors that the evaluation has a relatively small impact on the board. In the Rock Center for Corporate Governance Survey, we saw that 80% of the companies conducted a formal evaluation process, but that only 55% of these companies performed an individual evaluation on directors. Only one-third of the directors believed their company did a very good job of accurately assessing individual performance. It is also worth mentioning that in the same survey, 62% of directors said they believed that their peers allow personal or past experiences to dominate their perspectives.

Although we find similar figures in the PwC Survey, where only 49% of directors stated that their board made changes as a direct result of their self-evaluations, it should be highlighted that 8% of directors say they have decided not to nominate a director due to the assessment results. This is important because the evaluation is not intended to annihilate the work of the board as a whole, its committees or individual directors, but to find eventual hindrances and take the necessary actions for contingencies. For example 26% of the changes in the board as a result of the evaluation were adjustment in the Board Committees.

Undoubtedly, the most challenging evaluation of the board comes in the form of the annual elections of directors, as the shareholders are the ones who call the shots when it comes to assessing the performance of the Board by supporting or opposing the re-election of a director. At least 90% of the S&P 500 [4] have annual elections. Conversely, in some European jurisdictions like Spain, we find that directors can be appointed for four-year terms, although some companies have internal regulations stipulating a shorter term.

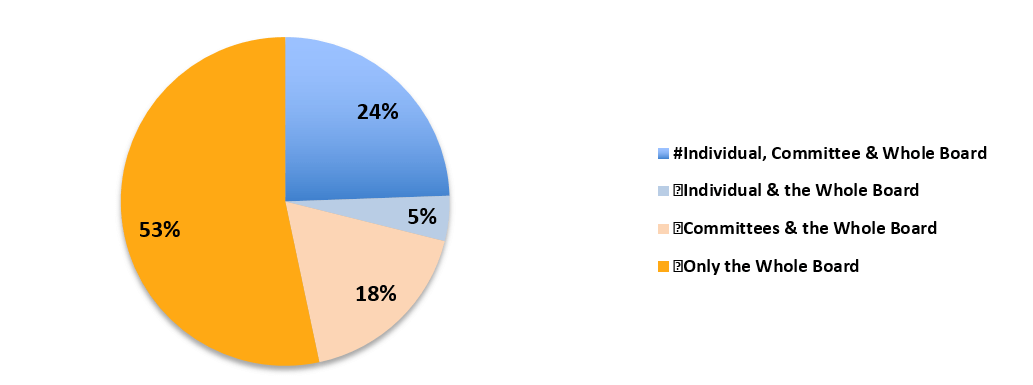

In the national corporate governance codes, we searched for specific mentions and suggestions regarding the assessment of the performance of the whole board, individual members and/or committees, which can be seen in the chart below. Note that the main issue dealt with by the majority of the codes is the importance of assessing the whole board.

Internal or external?

We finally come to the question of who is qualified to help the board of directors assess its performance, composition and structure. In terms of good governance, the lead independent director or the chairperson may conduct the process, but nevertheless, companies need to take a step back and look closely at the nomination and appointments committees. These committees should be composed primarily and chaired by directors with proven proficiency and skills in talent management, assessment and leadership. The committee must propose the best procedure to the board for conducting the assessment of the governing bodies, the individuals and (as a separate issue) the chairperson.

According to the E&Y [5] numbers, 29% of the S&P 500 have an independent chair, while 59% of the companies have appointed a lead independent director. As an alternative, the procedure can be triggered or led by the chair of the nominations committee or the board secretary. For family-owned companies, our experience is that a shareholder who is a family member will usually start the evaluation process. In order to avoid future or current tensions an external advisor is generally used, in order to objectively address any potentially disruptive family issues.

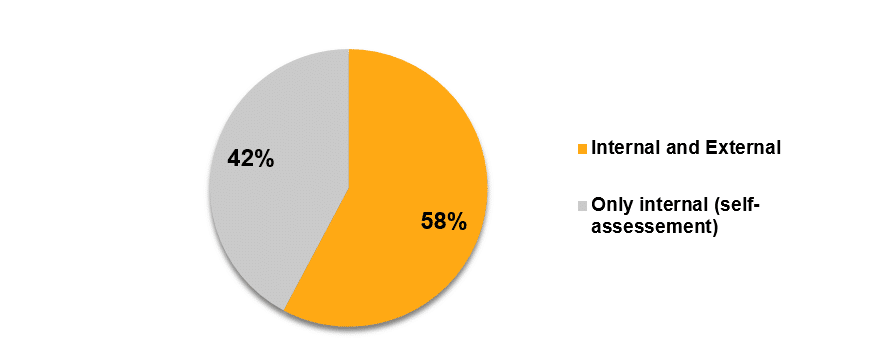

Companies often need both an internal and an external methodology to assess the board's performance. The external part of the question is simple: an outside entity is invited in to assist with the evaluation, bringing expertise, objectivity and fresh air to the process, while serving as a catalyst to facilitate dialogue and add value to the conclusions of the evaluation. Some may argue that the extra costs incurred by the external party are unnecessary, however an appropriate and well-chosen external advisor should be considered as an investment, especially if the external advisory team has experience in these assessments, the company's sector and corporate governance in general.

The self-assessment is very important for large companies and should be an on-going process, understanding and quantifying the soft skills and relationships that each director has cultivated in their role. Internal evaluations are extremely helpful in a system that fosters constant improvements to processes, and it is highly recommended to use the evidence from both going forward.

58% of national corporate governance codes suggest or recognise the value of an external independent party to help the boards conduct their evaluations.

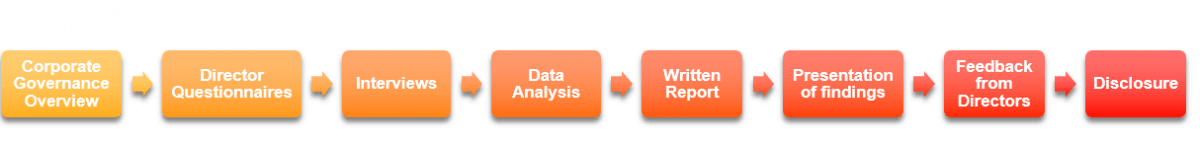

Methodology, metrics, and evaluation

This may be the most straightforward aspect of implementing a board evaluation. When the board’s goals are laid out, the corresponding KPIs must be set in order to determine relative success and achievement levels.

The goals must be set within a strategic plan with short-term and long-term targets, combined with an action plan. The assessment must not only evaluate whether the boards are working towards the goals in the best interests of the company and shareholders, but also to establish whether the established strategy still makes sense over time. The board must also assess that proper checks and balances are being put into place and working effectively, by reviewing on-going bases with sufficient time and dedication, internal controls, interaction with the external auditing, compliance and managing potential conflicts of interests.

Moreover, it is important to assess board dynamics, essentially based on the perception by board members of whether each one of their peers exhibits good or poor behaviour, goes prepared to the meetings, asks appropriate and challenging questions and enriches the culture of debate. The evaluation must assess the directors’ ability to access, process and discuss information thoroughly, Directors’ level of attendance is also key.

Compliance with the standards of governance shall be measured according to the shareholders’ structure and expectations, as well as those of the board members’ peers. If there is any deviation from a particular standard, the board should take the risks and benefits into account, and take measures that mitigate such risks.

Depending on the area to be assessed, the best metric to use may be satisfaction levels, agreement or compliance, but this will be up to the advisor to decide.

Most methodologies consist in very specific steps, but ultimately leadership on the process and cooperation of Directors will make the evaluation a successful tool.

Although questionnaires are very useful and provide confidentiality, they do not always allow a broad picture to be seen. They should therefore not be the only tool which is used to assess the board’s performance, and even though the use of a questionnaire helps to provide standardised answers, the questions should be tailored to fit the specific company.

Follow-up interviews and discussions with directors must then be used to explore and expand the answers from the questionnaires.

The evaluation topics are key to understand the current position of the board, and should include many new aspects which were not taken into account in recent years:

- Shareholder engagement

- Usage of social and regular media

- Compliance

- Recruitment and compensation policies

- Adjustment in corporate government policies

- Corporate social responsibility, e.g. environmental and social issues. Boards cannot afford to dismiss topics such as gender equality and equal pay, anti-bribery measures and whistleblowing procedures.

Results, consequences, and further Steps

This is where accountability comes into play. The process needs to be a positive one – both when highlighting successes, and identifying areas of improvement.

It’s very important for directors to embrace the evaluation methodology, so that they accept and have confidence in the results. In the Rock Center for Corporate Governance Survey, we saw that only 78% of directors seemed to be satisfied with the evaluation process. If the methodology is accepted with confidence, so will the results.

The next step is to draft an action plan, which will execute the necessary adjustments needed to build on the recommendations of the evaluation, always with the goal of reaching a better balance, and achieving the targets set in the strategy.

The action plan must highlight areas for improvement, the leaders responsible, the level of priority and the timetable.

If the evaluation shows a lack of experience and skills in a particular area such as Technology or Governance, one suggested action could be to revisit the board’s skills matrix, and take this into consideration for the next appointment. If the board does not appear to be dealing effectively with under-performing directors, an array of potential actions can be suggested, including training, the readjustment of specific committees, or ultimately the removal of the director.

In terms of disclosure, it seems only natural for privately-held companies to keep their evaluations in-house and confidential in order to conduct the changes necessary. Nonetheless, it is highly recommended for these companies to conduct board evaluations on a regular basis, as owners should be prepared for the day that a private equity firm asks for this data before it makes a decision on whether to inject capital. For listed companies, investors often welcome efforts at corporate openness and good disclosure. In 2014, the Council of Institutional Investors published: “Best Disclosure: Board Evaluation” and in 2016 LGIM (one of the most significant institutional investors in the UK) published the Active Ownership Report, which praised the evaluation reports of several companies.

Sources:

http://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-should-board-directors-evaluate-themselves/

https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/in/Documents/risk/Corporate%20Governance/in-cg-performance-evaluation-of-boards-and-directors-noexp.pdf

http://www.icaew.com/en/technical/corporate-governance/uk-corporate-governance/board-evaluations-and-effectiveness-reviews

~~~

[1] OECD Corporate Governance Factbook 2017

[2] Goshen Report from Israel. (English available traslation)

[3] Governance Insights Center PwC’s 2016 Annual Corporate Directors Survey.

[4] The EY Center for Board Matters: Governance in Numbers

[5] Idem.

Alberto Bocchieri is a Partner, Co-Head of Iberia & Latin America at Pedersen & Partners, based in Madrid. Prior to joining the firm, Mr. Bocchieri has held various senior level positions in large corporations in the chemical industry, banking and communications sectors in Brussels, Rome and Madrid. Mr. Bocchieri brings a wealth of Executive Search experience having previously worked for an international executive search firm. His areas of expertise include Private Equity, Corporate and Investment Banking, Legal and Financial Services, Professional Advisory Services, Energy (Mining, Oil & Gas, large utilities, Renewable and Conventional Power) and Industrials. He focuses on top executive positions and cross-border assignments both in Western and emerging economies. Mr. Bocchieri is a Graduate in Economy and Business from LUISS University in Rome. He completed the PADE Senior Management Program at IESE Business School in Madrid and the Global Senior Management Program at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and IE Business School. Mr. Bocchieri was distinguished in 2010 with the honorific title of “Cavaliere dell’Ordine della Stella” from the Italian Republic. He is bilingual in Italian and Spanish, and speaks fluently English and French.

Alberto Bocchieri is a Partner, Co-Head of Iberia & Latin America at Pedersen & Partners, based in Madrid. Prior to joining the firm, Mr. Bocchieri has held various senior level positions in large corporations in the chemical industry, banking and communications sectors in Brussels, Rome and Madrid. Mr. Bocchieri brings a wealth of Executive Search experience having previously worked for an international executive search firm. His areas of expertise include Private Equity, Corporate and Investment Banking, Legal and Financial Services, Professional Advisory Services, Energy (Mining, Oil & Gas, large utilities, Renewable and Conventional Power) and Industrials. He focuses on top executive positions and cross-border assignments both in Western and emerging economies. Mr. Bocchieri is a Graduate in Economy and Business from LUISS University in Rome. He completed the PADE Senior Management Program at IESE Business School in Madrid and the Global Senior Management Program at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and IE Business School. Mr. Bocchieri was distinguished in 2010 with the honorific title of “Cavaliere dell’Ordine della Stella” from the Italian Republic. He is bilingual in Italian and Spanish, and speaks fluently English and French.

Paola Gutierrez Velandia has over sixteen years of market leading expertise in working with a wide range of clients and key stakeholders in the areas of corporate governance, board services, shareholder engagement, and public affairs across Latin America, US, MENA, and Central Europe. Moreover, she has extensive experience in emerging markets, where she has led board assessments, due diligences and corporate governance advisory projects for listed and privately owned entities. Ms. Gutierrez Velandia participated actively in the Free Trade Area of the Americas negotiations between the US Government and Colombia, specifically on the issues of intellectual property, procurement, and foreign investment for the pharmaceutical sector. Earlier in her career, Ms. Gutierrez Velandia led and developed the corporate governance units and departments for the Colombian Confederation of Chambers of Commerce and for a corporate consulting firm from Spain. Ms. Gutierrez Velandia also served as Spain & Latin America Director for Georgeson, a world leader in shareholder services and proxy solicitation. At Georgeson, she established the company’s regional strategy to develop corporate governance advisory services for top-level publicly listed corporations and investors. Ms. Gutierrez Velandia is a renowned author of research papers in the fields of corporate governance, board evaluation, shareholder engagement and governance risk management published in international and national journals and magazines.

Paola Gutierrez Velandia has over sixteen years of market leading expertise in working with a wide range of clients and key stakeholders in the areas of corporate governance, board services, shareholder engagement, and public affairs across Latin America, US, MENA, and Central Europe. Moreover, she has extensive experience in emerging markets, where she has led board assessments, due diligences and corporate governance advisory projects for listed and privately owned entities. Ms. Gutierrez Velandia participated actively in the Free Trade Area of the Americas negotiations between the US Government and Colombia, specifically on the issues of intellectual property, procurement, and foreign investment for the pharmaceutical sector. Earlier in her career, Ms. Gutierrez Velandia led and developed the corporate governance units and departments for the Colombian Confederation of Chambers of Commerce and for a corporate consulting firm from Spain. Ms. Gutierrez Velandia also served as Spain & Latin America Director for Georgeson, a world leader in shareholder services and proxy solicitation. At Georgeson, she established the company’s regional strategy to develop corporate governance advisory services for top-level publicly listed corporations and investors. Ms. Gutierrez Velandia is a renowned author of research papers in the fields of corporate governance, board evaluation, shareholder engagement and governance risk management published in international and national journals and magazines.

Pedersen & Partners is a leading international Executive Search firm. We operate 56 wholly owned offices in 52 countries across Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia & the Americas. Our values Trust, Relationship and Professionalism apply to our interaction with clients as well as executives. More information about Pedersen & Partners is available at www.pedersenandpartners.com

If you would like to conduct an interview with a representative of Pedersen & Partners, or have other media-related requests, please contact: Diana Danu, Marketing and Communications Manager at: diana.danu@pedersenandpartners.com